This week’s Torah portion covers the death and burial of our patriarch Jacob. You may recall that, because of a famine in Canaan, Jacob and his family moved to Egypt where Joseph, Jacob’s eleventh son, had been living and became a prominent member of Pharaoh’s court. Joseph was able to offer his father and other family members security while in Egypt. When the end of Jacob’s life was near, he expressed his desire to have his body moved from Egypt and buried with his own ancestors in Canaan: “I am about to be gathered to my kin. Bury me with my ancestors. [Then] he drew his feet into the bed and, breathing his last, he was gathered to his kin” (Genesis 49:29-33).

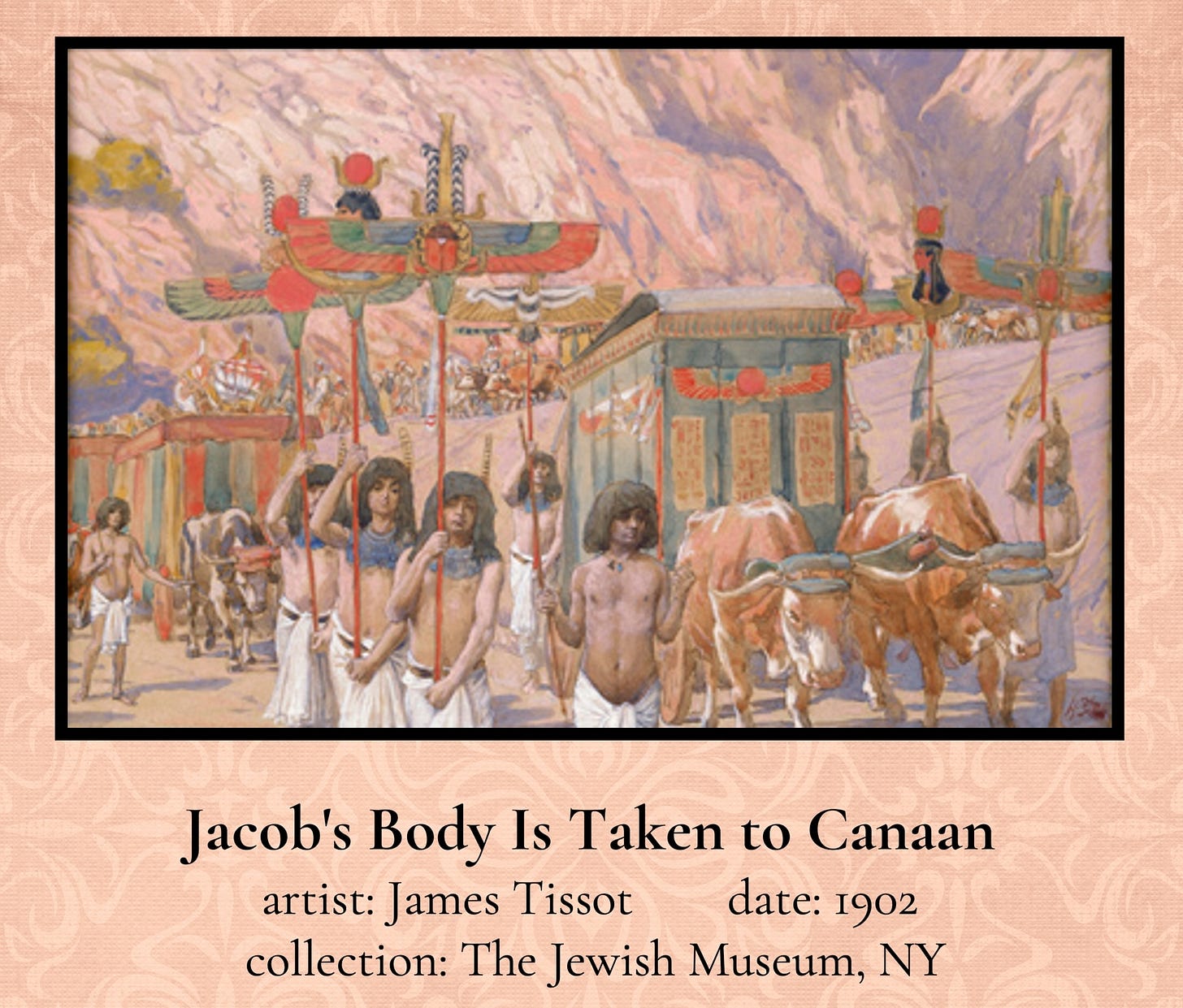

Traditionally, Jewish people bury their dead within 24 hours. The steps taken with Jacob’s remains did not follow this custom. Instead, Joseph asked his Egyptian physicians to embalm Jacob’s body, a process that required 40 days, and the Egyptians “bewailed” Jacob for a total of 70 days (Genesis 50:2-3). When Jacob’s body was ready to go to its final resting place in Canaan, the group attending the body included “all the officials of Pharaoh, the senior members of his court, and all of Egypt’s dignitaries, together with all of Joseph’s household, his brothers, and his father’s household ... Chariots, too, and horsemen went up with him; it was a very large troop” (Genesis 50:7-9). After a mourning period of seven days (Genesis 50:10), Jacob was buried with his ancestors, “in the cave ... which Abraham had bought for a burial site” (Genesis 50:13).

Events that do not follow the usual steps open the door for our ancient sages to debate their meaning. In the case of the burial of Jacob, the Torah provides more detail that further clouds the meaning of the text. For example, after Jacob died, Joseph approached Pharaoh and claimed that Jacob told Joseph that his body should be buried “in the grave which I made ready for myself” (Genesis 50:5). But the grave that Jacob is buried in is the same cave that Abraham, Jacob’s grandfather, purchased. Jacob had nothing to do with preparing this site for his own burial, so what is this text referring to?

Also, the Torah tells us that a group of Canaanites observed the mourners, who were mostly Egyptian, at a location called Goren ha-Atad, or literally,

“threshing floor of the thornbush.” Acknowledging the solemnity of the event, the Canaanites named the place “the mourning of the Egyptians” (Genesis 50:11). In other parts of the Torah, the Canaanites are referred to as corrupt and condemned. Why are they singled out here for noting the procession and naming the location?

To see what the ancient sages had to say about these questions, we turn to the Talmud. The Judaism we practice today is not the religion of the Torah, with its animal sacrifices in the Temple. That religion can more accurately be called the Israelite religion. The Judaism we practice today has its foundation in the Talmud.

Reading the stories in the Torah, we may find that Jacob’s twin brother Esau is someone we could relate to. The sibling rivalry between Jacob and Esau begins in the womb and continues through their formative years. It probably does not help that their father Isaac favored Esau over Jacob. Troubles that are outlined in the Torah include when Esau is starving and Jacob has food, but Jacob withholds the food until Esau agrees to forfeit his birthright. Also, when their father is dying and asks Esau to prepare a stew for him before giving him his final blessing, Jacob prepared a stew and tricked his father into believing he was Esau and received the blessing instead. We might understand why, after years of this rivalry, Esau muttered under his breath, I am going to kill my brother. Would he have really killed Jacob? We don’t know because Jacob fled and was gone for many years. When Esau and Jacob do meet again, they seem to reconcile. The Torah does not give us solid reason to believe that Esau is a bad person. But the Talmud does.

With thanks to Dr. Malka Simkovich of the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, Rabbi Jaech shared with us how the ancient sages interpreted these passages. In ancient times, a threshing floor may have been surrounded by thornbushes to keep wild animals out. Similarly, the large group of mourners for Jacob surrounded the casket with crowns to keep enemies, like the Canaanites, away. But in this case, the enemies are identified as being the children of Esau, the brother with whom Jacob had long-standing issues; the children of Ishmael, the banished son of Abraham; and the children of Keturah, who became Abraham’s wife after

the death of Sarah. The Talmud tells us that these people came to wage war with the group of mourners (Babylonian Talmud, Sotah 13a).

In this Talmudic midrash, the enemies have a change of heart and join the mourners. But there are additional midrash that paint Esau in a negative light. Building on the line where Joseph claims to Pharaoh that Jacob had prepared his own plot, a Talmudic midrash claims that there were only four spots in the burial site: one for Isaac, one for Rebekah, one for Esau and one for Jacob. But Jacob buried his wife Leah there, which meant there was only one spot left—and Esau claimed that for his own.

Jacob’s descendants try to convince Esau that, when Esau forfeit his birthright to Jacob, he also forfeit his reserved plot. Esau asks for proof that he forfeit his spot, but Jacob’s grandson puts an end to discussion by clubbing Esau over the head, at which point Esau’s “eyes popped out and fell on Jacob’s legs. Jacob opened his eyes and smiled” (Babylonian Talmud, Sotah 13a) because of the triumph of revenge.

A later version from the Targum has a similar story, but with a subtle change. This time the grandson “unsheathed the sword and struck off the head of the Wicked Esau ... Esau’s head rolled into the midst of the [burial] cave, and rested upon the bosom of his father, Isaac” (Targum Pseudo- Jonathan). Although this is still a horrific murder of Esau, Rabbi Jaech appreciates that this shows that, as his father’s favorite, Esau could not have irredeemable.

Rabbi Jaech points out that it is very human for us to think of people as either all good or all bad. But people are more complicated than that. Perhaps these different tales tell us that the passage of time allows us to change our perception of people, which may result in less harsh judgment of others.

This blog is Tara Keiter’s interpretation of the Temple Israel of Northern Westchester Torah Study session. Misquotes or misunderstandings in what Rabbi Jaech taught are the responsibility of Tara Keiter.